Blog 08/05/2021 - Suni Lee & the Hmong's Secret War

When gymnast Sunisa "Suni" Lee stepped up to lead the USA to the silver medal in the Women’s Team Gymnastics competition at the Tokyo Olympics, the world took notice. She followed that with an even greater achievement with the all-around gold medal, Lee became the first Asian American to claim the most prestigious Olympic Gymnastics title. She wasn’t just representing Team USA; she was also representing the Hmong community around the world. She became the fifth consecutive American woman to accomplish the feat, following in the footsteps of Carly Patterson at the 2004 in Athens, Nastia Liukin in 2008 at Beijing, Gabby Douglas in 2012 in London and Simone Biles in 2016 in Rio de Janeiro. Lee has now vaulted into the pantheon of legendary USA gymnasts. Her win is being celebrated across the USA, but it’s especially meaningful for the Hmong community as Suni, of St. Paul, MN, is the first Hmong American Olympian.

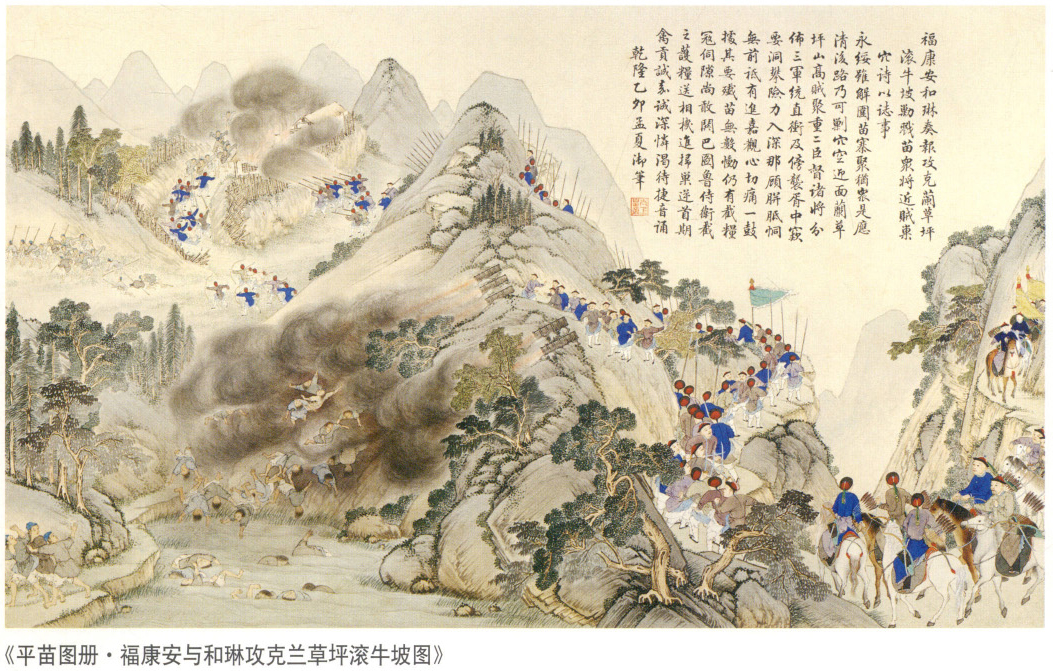

Many people (and I’m being polite) don’t have a clue who the Hmong people are or how Suni’s family came to reside in Minnesota. MHT salutes Suni, the Hmong people for their support of the USA and all the athletes who participated in the Olympics and made us all proud. In China for centuries, the Hmong lived autonomously in remote areas, retaining a unique culture despite ongoing conflicts with the Qing Dynasty of Imperial China. Like today, Chinese rulers used military might to suppress ethnic minorities. While the Hmong lived in south-western China, their Manchu overlords had labeled them 'Miao' and targeted them for genocide when they defied being humiliated, oppressed, and enslaved. "These conflicts resulted in a mass exodus by the Hmong to the mountainous regions of Southeast Asia, an area known today as Laos, Myanmar (Burma), Thailand, and Vietnam. “We always knew that our history was rooted in China. However, our ancestors never got along with the Imperial Chinese. They invaded our lands. Killed our people. This went on for hundreds of years. Many Hmong leaders and their families, including my great-grandparents, moved to Laos to escape being persecuted.” Maj Cher Cha Vang, military and Hmong leader.

In 1893, the Kingdom of Laos became a French colony as part of French Indochina. The Laotian Hmong, as many as 30,000, were heavily taxed and oppressed by French and Laos authorities. By the early 1900s, the French and Laotian authorities found it easier to let Hmong leaders deal directly with Hmong issues. When the Hmong people increased in numbers and became prosperous, one of them became the local official who worked hard to quickly settled every small dispute so that the villages could make their living peacefully.

During World War II, known by the Hmong community as the Japanese War, most stayed loyal to the French and the Royal Lao Government; the rest joined the Communist Party (Pathet Lao.) The pro-French Hmong showed fierceness against the Japanese while they were extending their reach over Southeast Asia. As a result, the Hmong were officially recognized as citizens of Laos in 1947.

At the end of WWII, the French attempted to reassert control over their former colonies in Southeast Asia, but were fiercely opposed by Chinese-backed Communist forces in Vietnam and Laos. Many Hmong were to be drawn into the new war that engulfed the entire region. During the 1954 siege at Dien Bien Phu, 500 Hmong soldiers were sent from Laos to assist the French Paratroopers & Foreign Legionnaires. They didn’t reach the surrounded French strongpoint before they surrendered to the Communist Viet Minh ending French colonial rule in Southeast Asia.

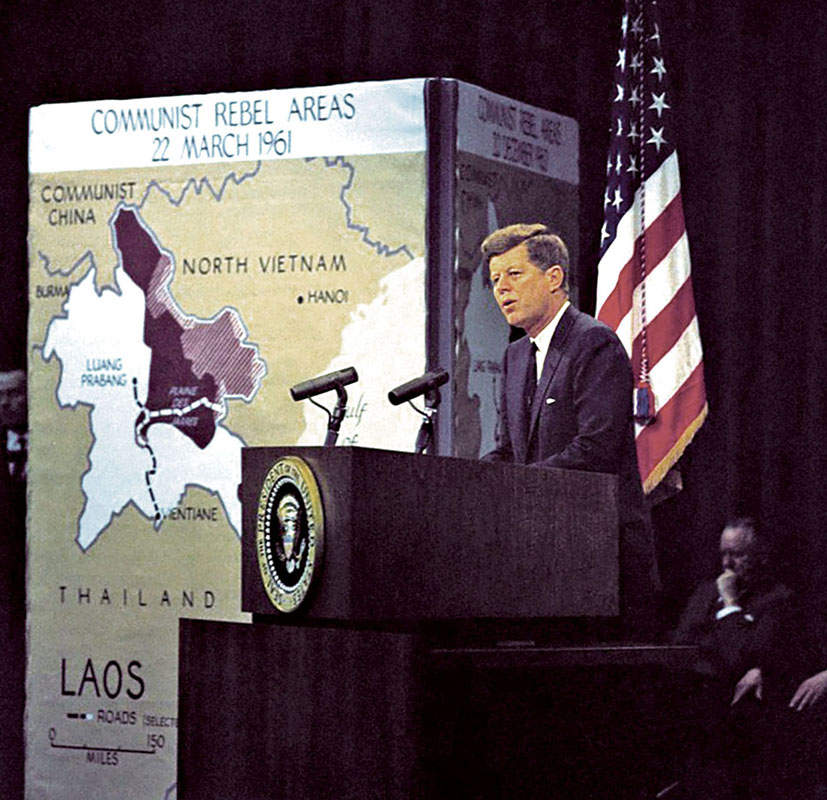

Everything changed for the Hmong when newly elected US President John F. Kennedy authorized ethnic minorities to be recruited to participate in covert military operations against the spread of communism in Laos. The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) agents met with the young Hmong military officer Vang Pao to carry out Kennedy’s objectives.

The recruitment of Hmong irregular troops, supported by U.S. Special Forces and CIA advisers, along with huge drops of military supplies & tons of food by Air America aircraft (Air America was the CIAs own air force with the motto: “Anything, Anywhere, Anytime, Professionally,” signaled the start of what is now called the Secret War.

Note: The fresh green paint over all the markings including the MARINES on the tail.

This was despite President Kennedy’s press conference statement on 23 March 1961, “I want to make it clear to the American people, and to all of the world, that all we want in Laos is peace, not war—a truly neutral government, not a cold war pawn, a settlement concluded at the conference table and not on the battlefield. Our response will be made in close cooperation with our allies and the wishes of the Laotian government. We will not be provoked, trapped, or drawn into this or any other situation but I know that every American will want his country to honor its obligations to the point that freedom and security of the free world and ourselves may be achieved.”

In 1962 the CIA set up a headquarters for MajGen Vang Pao in the Long Tieng valley, which at that time had almost no inhabitants. By 1964, a runway had been completed and by 1966 Long Cheng was one of the largest US installations on foreign soil and one of the busiest airports in the world at the “most secret place on Earth!”

Of the 300,000 Hmong population in Laos, more than 19,000 men were recruited into the CIA-sponsored secret operation Special Guerrilla Units (SGU) while some enlisted as Forces Armees du Royaume, the Laotian royal armed forces. U.S. Army Special Forces arrived to train both the Hmong irregular troops as well as the Royal Loa Army soldiers.

The U.S. funded new schools throughout the remote regions of Laos, which opened opportunities to Hmong girls. As the war escalated, some Hmong girls were trained as nurses and medics to care for wounded soldiers.

1968 and 1969 were the two worst years for both the American War in Vietnam and the Secret War in Laos. 18,000 Hmong soldiers were killed in combat, in addition to thousands more civilian casualties. By 1969, Hmong troop strength was nearing 40,000. Under the new administration of President Richard Nixon, U.S. bombing of Laos escalated but support became more difficult when the U.S. Congress learned of the CIA’s Secret War in Laos.

By 1971, the Secret War was weighing heavily on the Hmong and the people of Laos. The estimate KIA toll for Hmong soldiers was 3,000, with 6,000 more WIAs. Hmong boys were becoming involved as the average age of recruits that year was 15. Still the Hmong were hindering the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) from sending troops and supplies into South Vietnam using the Ho Chi Minh Trail plus rescuing downed American pilots in Laos. Col Walter Boyne said, “By this time, Air America was keeping some 170,000 Hmong refugees alive with airdrops of rice, a situation that had gone on so long that Hmong children were said to believe that rice was not grown but simply fell from the sky.”

In 1975, NVA and Pathet Lao units captured the Royal Lao positions on the strategic Plain of Jars (with the ancient stone jars.) After South Vietnam fell to Communist North Vietnam invasion, Gen Vang Pao and about 2,500 Hmong military forces and family members were airlifted from Long Cheng Air Base to Thailand. As many as 30,000 other Hmong crowded into Long Cheng, hoping for escape.

The Secret War cost between 30,000 and 40,000 Hmong soldiers KIA and between 2,500 and 3,000 MIA. An estimated one-fourth of all Hmong men and boys died fighting the Communist Pathet Lao and the NVA. The official US military death total in the entire Vietnam War exceeded 58,000. About 50,000 Hmong civilians had also been killed or wounded in the war. As CIA Director William Colby said, “For 10 years, Vang Pao’s soldiers held the growing North Vietnamese forces to approximately the same battlelines they held in 1962. And significantly for Americans, the 70,000 North Vietnamese engaged in Laos were not available to add to the forces fighting Americans and South Vietnamese in South Vietnam.”

After the Communist Pathet Lao overthrew the Laotian monarchy (subsequently sending the Royal family for reeducation to never be seen again), they launched an aggressive campaign to capture or kill Hmong soldiers and families. Thousands of Hmong were evacuated or escaped on their own to Thailand. Thousands more who had retreated deep into the jungle were left to fend for themselves, which led to the creation of the Chao Fa and Neo Hom freedom fighter’s movements. Many men took up arms again to protect their families as they crossed the heavily patrolled Mekong River to safety in Thailand. Any Hmong caught in Laos returned to Laos from Thailand met the same fate as the Royal Family, reeducation camp for a bullet in the back of the head and a shallow grave.

The Hmong began moving into refugee camps in Thailand and the first Hmong family to resettle in Minnesota arrived in November 1975. The largest wave came after the passage of the US Refugee Act of 1980. In 2004, the final temporary shelter for 15,000 Hmong remaining in Thailand closed. The “last wave” came to the US, with as many as 5,000 settling in established Minnesota Hmong communities.

The 2010 U.S. census recorded more than 260,000 Hmong with over 66,000 of that number living in Minnesota, most of them in or near the Twin Cities, the largest urban population of Hmong in America. As Lionel Rosenblatt, Head of the Refugees International clearly states, “Here were thousands of Hmong, many of whom spoke American military lingo and had names likes ‘Lucky’ and ‘Judy’ and ‘Bison’ and who had been soldiers, radio operators, pilots, and CIA operatives in a war unknown to the American public.

This was unacceptable. How could the U.S. abandon these people? If the United States owed gratitude to anyone in Southeast Asia it was the Hmong.” If the South Vietnamese, Laotian and Cambodian soldiers had fought with the tenacity of the Hmong the results in South East Asia might have stemmed the murderous communist reeducation genocides of the 1970s.

MHT Group in Laos.

Congratulations again to Suni Lee for so proudly representing both the USA and her people.