Blog 08/09/2021 - Tinian: Atomic Bomb Island

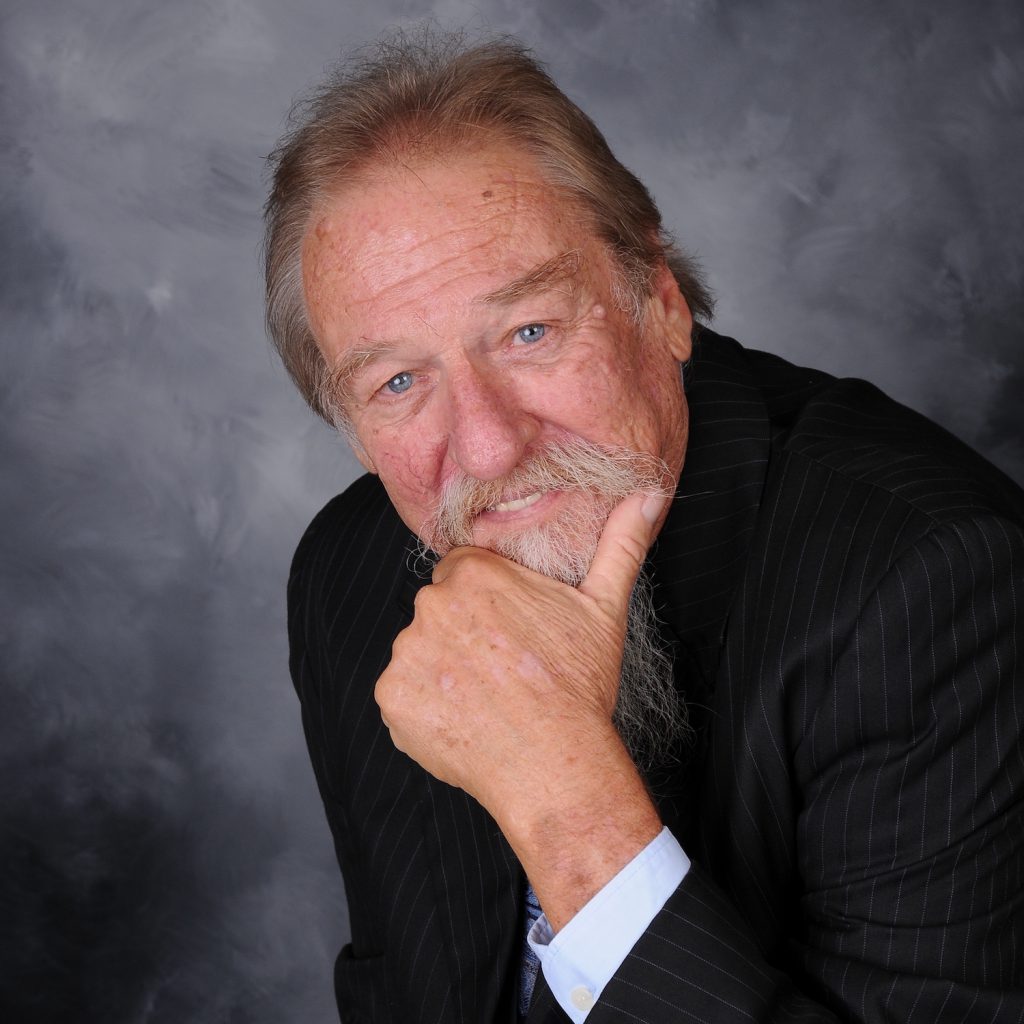

Tinian: Atomic Bomb Island by Author & MHT Tour Historian Don Farrell

MHT is lucky to have these excerpts from Don’s latest book as we reflect on the dual bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki during WWII.

Thanks to the in-depth advance planning by navy ordnance officer Captain Deak Parsons, the August 6, 1945, atomic strike mission to Hiroshima was essentially a “milk run.” [In WWII slang was a bombing mission flown that was routine and no casualties were incurred, at least not by the USAAF]

Although overloaded because of the five-ton Little Boy atomic bomb, extra fuel, and the two Manhattan Project [the code name for the American-led effort to develop a functional atomic weapon during WWII] weaponeers, Enola Gay lifted off from Runway Able, Tinian, at 0245, with The Great Artiste and Necessary Evil close behind. Eight minutes after they were airborne Parsons loaded the four silk bags of high explosive propellant into Little Boy.

Above: The B-29 Enola Gay in front of the “Little Boy” Bomb Pit. Below; The Bomb Pit on Tinian today.

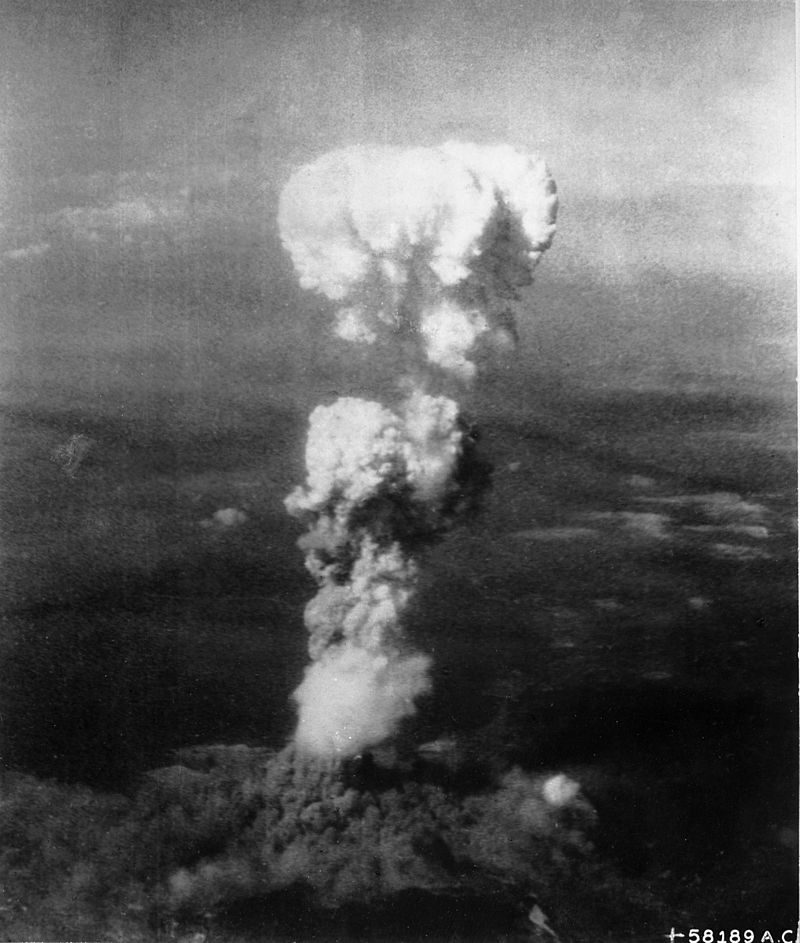

They successfully rendezvoused at Iwo Jima shortly after 0600. Tibbets [Colonel Paul Tibbets, USAAF who named his B-29 after his mother Enola Gay Tibbets] then informed the crew that the weapon they were carrying was an atomic bomb. They reached Hiroshima shortly after 0900, Tinian time. At 09:15:17, Little Boy was dropped, exploding at about 1,950 feet, crushing Hiroshima to the ground, and starting a series of fires.

The Enola Gay crew was mesmerized, then frightened, by the boiling mass of multi-colored fire and smoke that blanketed Hiroshima, then raced up toward them as they cruised at 39,000 feet. Then Ray Gallagher, the radio operator on Enola Gay, snapped out if it and hollered through his intercom, “if we don’t get out of here, were going to get caught in our own bomb blast.”

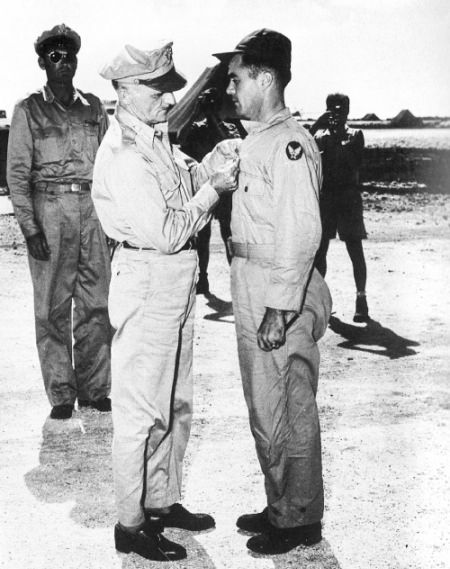

Enola Gay arrived back on Tinian at 2:58 P.M., where General Spaatz [Gen C.A. “Tooey” Spaatz, Commander of the U.S. Strategic Air Forces in the Pacific, directed the strategic bombing of Japan, including the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki] pinned the Distinguished Serve Cross on his chest with cameras rolling and the booze flowing.

Above: the B-29’s of the 509th Composite Group (left to right): Big Stink, The Great Artiste & Enola Gay.

The message of the successful drop reached President Truman while he was aboard the cruiser USS Augusta headed back to America from the Yalta conference: “Hiroshima bombed visually with one-tenth cloud cover. There was no fighter opposition and no flak.” He immediately directed that the media report that had been prepared by Major General Leslie Groves, commanding officer of the Manhattan Project, be released. Although the 509th strike teams [The 509th Composite Group (509 CG) was the USAAF unit created during WWII and tasked with the operational deployment of nuclear weapons] figured that the Japanese would surrender immediately, the Fat Man team immediately began preparing their bomb for another strike, should the Japanese not surrender.

Bright and early on the morning of August 7, copies of national newspapers arrived on Tinian, Saipan, and Guam, with photos of the now-famous mushroom cloud over Hiroshima on the front page. The $2 billion dollar secret that had been so carefully kept was now public knowledge around the world. With the combat correspondents stationed on Guam screaming for comments, Col. Tibbets and the senior officers from Enola Gay flew to Guam for a press conference.

After dealing with the press, Tibbets and representatives of the Manhattan Project met with General LeMay [Major General Curtis LeMay, USSAF, was Commanding General of XXI Bomber Command in the Pacific and in charge of all strategic air operations against the Japanese home islands] to discuss the next mission, if the Japanese did not surrender. The original order, approved by Truman, had clearly stated, “Additional bombs will be delivered on the above targets as soon as made ready by the project staff.”

Unfortunately, LeMay’s weather prognosticator now predicted bad weather would set in over Japan again by about August 10.

Above: Dr. Ramsey signs the “Fat Man”

Dr. Norman Ramsey, the senior physicist with the Manhattan Project on Tinian expressed his regret, “that the schedule could not be advanced two days instead of just one since good weather was forecast for 9 August and the following five days were expected to be bad. It was finally agreed that Project A (the bomb assembly team on Tinian) would try to be ready for August 9, provided that it was understood by all concerned that the advancement of the date by two full days introduced a large measure of uncertainty into the probability of our meeting such a drastically revised schedule.” He gave them a 70% probability of success.

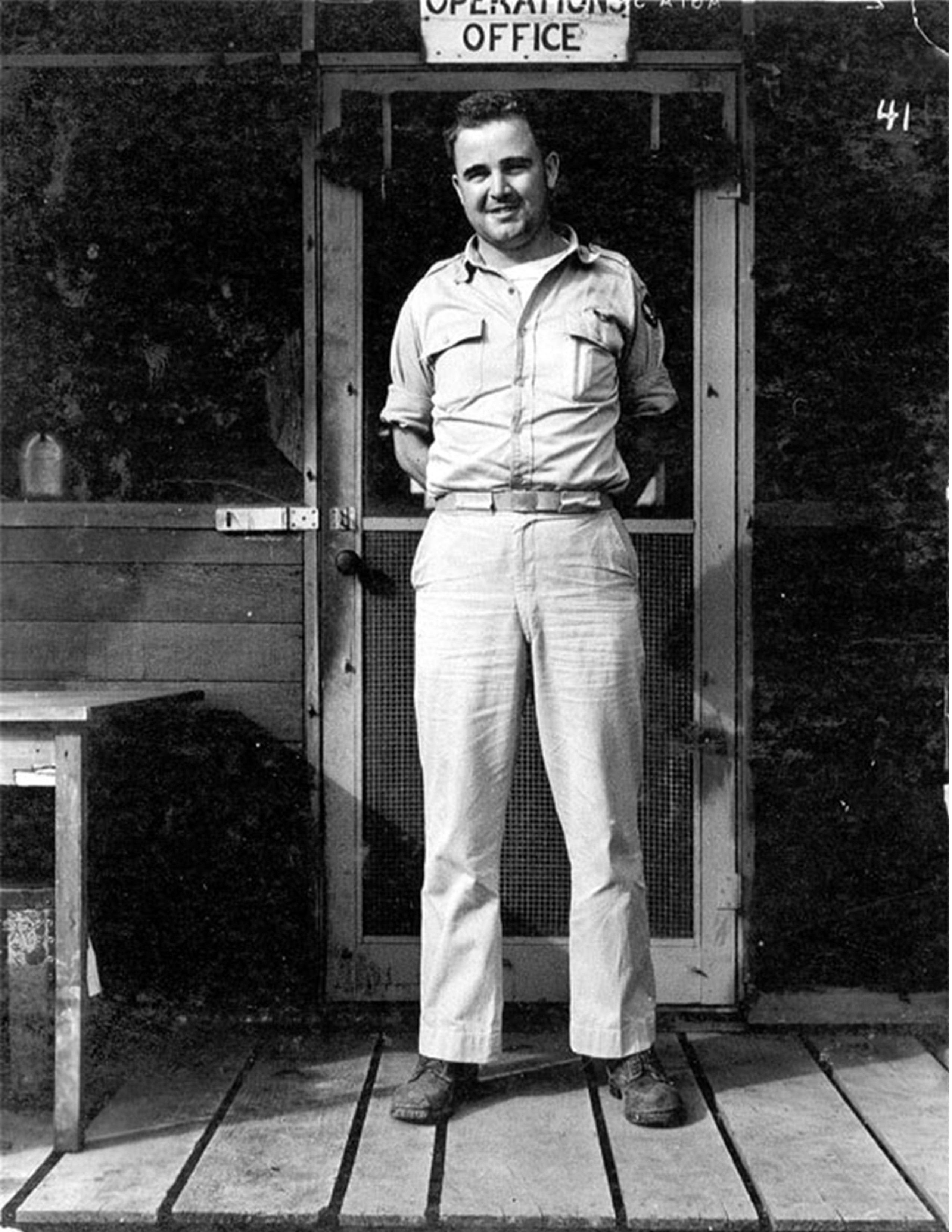

Tibbets then informed General LeMay that he would not fly the mission. He was assigning it to Major Charles Sweeney, [Commander of the 393d Bombardment Squadron, Heavy, the combat element of the 509th CG, in charge of 15 Silverplate B-29s and their flight and ground crews, 535 men in all] who had no combat experience. LeMay expressed concern, but Tibbets said that because Sweeney had successfully flown on his wing during the Hiroshima mission, he was qualified, and LeMay let it ride.

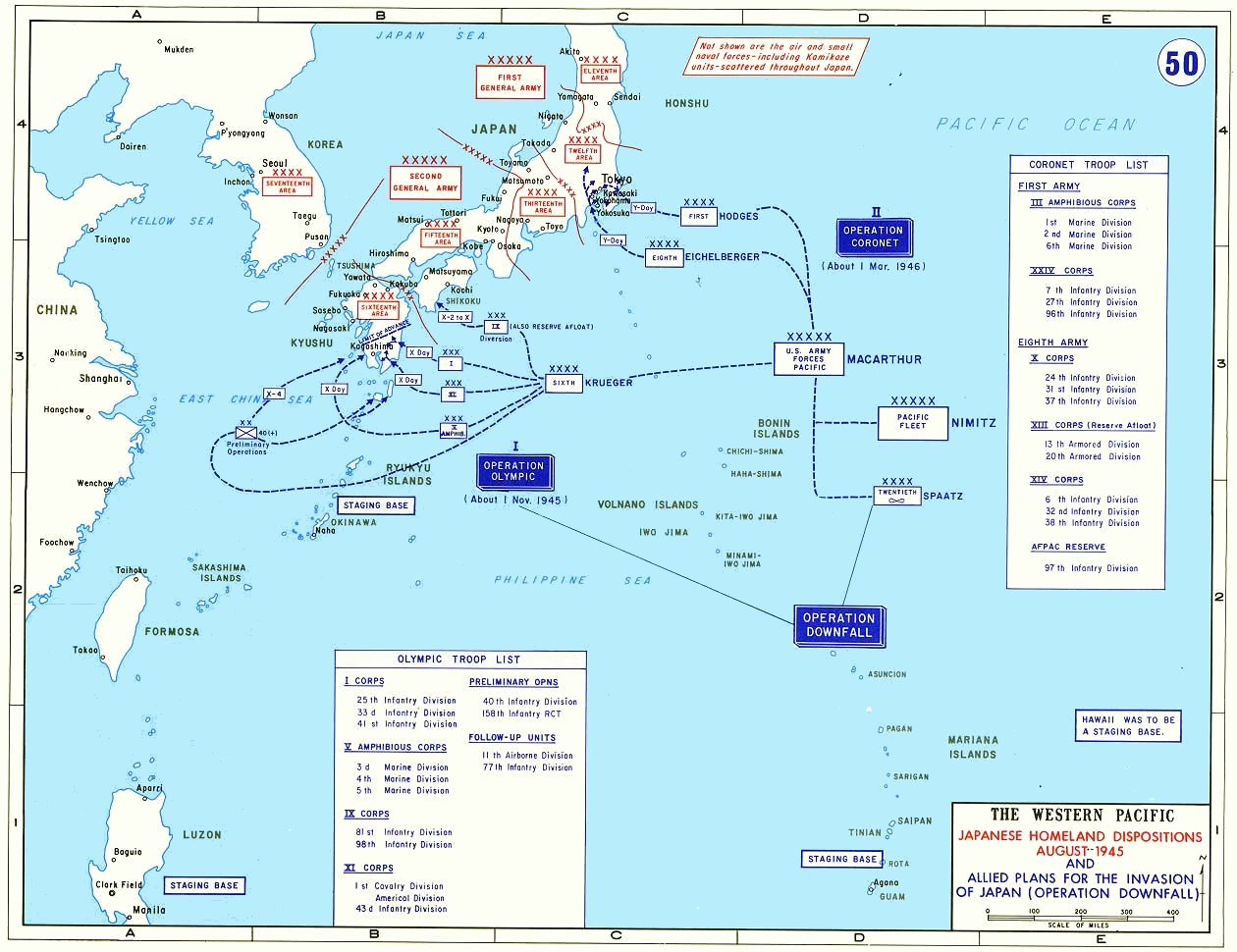

On the morning of August 8, and with no surrender from Japan, General Nathan Twinning, the new commanding officer of the 20th Air Force, handed the order for a second drop to General Spaatz, to pass on to General LeMay, to pass on to Col. Tibbets. “The 509th Bomb Group, using special munitions, will strike either Kokura or Nagasaki at approximately 091030K.” It would not happen at 091030, and it almost failed completely.

Whereas everything went perfectly on the Hiroshima mission, everything that could go wrong with the August 9 mission did go wrong. It was certainly no “milk run.”

The crews boarded their planes on time—0330. After firing up the engines on Bockscar, Sweeney shut her down and climbed out. The fuel transfer pump from the reserve tanks was not functioning. After a scolding from Tibbets, who told Sweeney he would not need the reserve tanks if he would fly straight to the rendezvous, then fly directly to Kokura, then fly directly to Nagasaki if Kokura could not be bombed visually, without waiting at either location for any reason. Sweeney got his crew back aboard ship and took off with no further problems.

Above: The Author (3rd from left) at Runway Able on Tinian.

Then, about 0710, the lights on the black box attached to Fat Man began to blink, telling the crew that the bomb was ready to detonate, giving everyone aboard a scare. It was corrected. Nonetheless, the strike team continued into the darkness with a sense of foreboding.

Then, when Bockscar made it to the rendezvous at Yakushima, Captain Fred Bock, USAAF joined him with The Great Artiste, but Major James Hopkins, USAAF flying the Big Stink, failed to show. Instead of leaving immediately for Kokura, Sweeney circled around burning fuel for another forty-five minutes.

By the time Sweeney and Bock made it to Kokura, it was covered with smoke and haze. Instead of heading directly to Nagasaki, Sweeney made three passes over Kokura, burning more fuel. Now with fuel so low they would not be able to make it to Iwo Jima, Sweeney turned southwest for a run at Nagasaki. They would have to try a landing at Okinawa, where no B-29 had gone before.

Above: Navy CDR Dick Ashworth, USN

This time Sweeney had no choice. They only had enough fuel, for one run at the target, maybe. If they did not drop it, they would have to land on Okinawa with a live atomic bomb or drop it in the ocean. When Sweeney asked Commander Dick Ashworth, USN the bomb commander on this mission, if they could drop by radar, he said, “No.” Their orders were clear, they had to drop visually; the bombardier had to see the target through the crosshairs of his bombsite.

As they approached Nagasaki, Murphy’s Law prevailed. It appeared socked in. Finally, Ashworth grimly announced they could make a radar run. The crew joyfully attended to their business. Then, at the very last moment, combat bombardier Captain Kermit Beahan shouted, “I can see it! I’ve got it!” And with only a couple of quick course corrections, he let Fat Man fall at 12:02 P.M. “Bombs Away!” Then corrected himself, “Bomb away!”

Now Sweeney set a course for Yontan Airfield, Okinawa. There, with no radio contact, Sweeney made a successful “crash landing”, just as two engines died from fuel starvation. Once on the ground, they determined that Fat Man had fallen directly on the Mitsubishi Arms and Steel Works, where the torpedoes had been manufactured that were used at Pearl Harbor.

Sweeney took on half a tank of gas and took off for Tinian, arriving there at 11:06 P.M. There were no movie cameras, no wild party, nothing but leftovers from the galley and extra rations of medicinal alcohol, and plenty of non-medicinal alcohol at the officers’ club. The last of them finally hit the sack at 0345. At 0645 that morning, August 10, 1945 Tokyo Time, the Japanese government transmitted their acceptance of the Potsdam Declaration – unconditional surrender – to the Swiss and Swedish embassies.

It had not been pretty, but Sweeney, Ashworth, and crew had finished the job.

All quotes from Farrell, Don. Atomic Bomb Island: Tinian, The Last Stage of the Manhattan Project, and the Dropping of the Atomic Bombs on Japan in World War II. Stackpole Books: Guilford Connecticut, 2019. Now available at Barnes and Noble outlets and Amazon Books.

Editor’s Note: The “Little Boy” atomic bomb with a blast yield equivalent to 16 kilotons of TNT was detonated over the city of Hiroshima. The radius of total destruction was about one mile with 69% of buildings destroyed; 70,000–80,000 people (30% of the city's population) were killed by the blast and resultant firestorm and another 70,000 injured. Out of those killed, 20,000 were Imperial Japanese Army soldiers and 20,000 Korean slave laborers working in the munition factories.

The "Fat Man" nuclear bomb with a blast yield equivalent to 21 kilotons of TNT was detonated over the city of Nagasaki. About 44% of the city was destroyed; 35,000 people were killed and 60,000 injured.

Thanks to “Little Boy” and “Fat Man” over 30 million American and Japanese lives were saved as the two bombs convinced the Imperial Japanese Emperor to overrule the fanatics who had warped the “Bushido Code” that everyone must die defending the Japanese mainland.

Above: Don (second row – far right) with a MHT Tour Group

MHT appreciates Don Farrell taking the time to support our Blog and we recommend everyone interested in this interesting subject read more about it by ordering the book:

https://www.amazon.com/Atomic-Bomb-Island-Manhattan-Dropping/dp/0811739619/ref=asc_df_0811739619/?tag=hyprod-20&linkCode=df0&hvadid=459724879118&hvpos=&hvnetw=g&hvrand=3518446754762511739&hvpone=&hvptwo=&hvqmt=&hvdev=c&hvdvcmdl=&hvlocint=&hvlocphy=9008161&hvtargid=pla-931551662568&psc=1