Blog 01/12/2023 - WWII Japanese Holdouts

Imperial Japanese Army Soldiers & Sailors Who fought on Throughout the Pacific

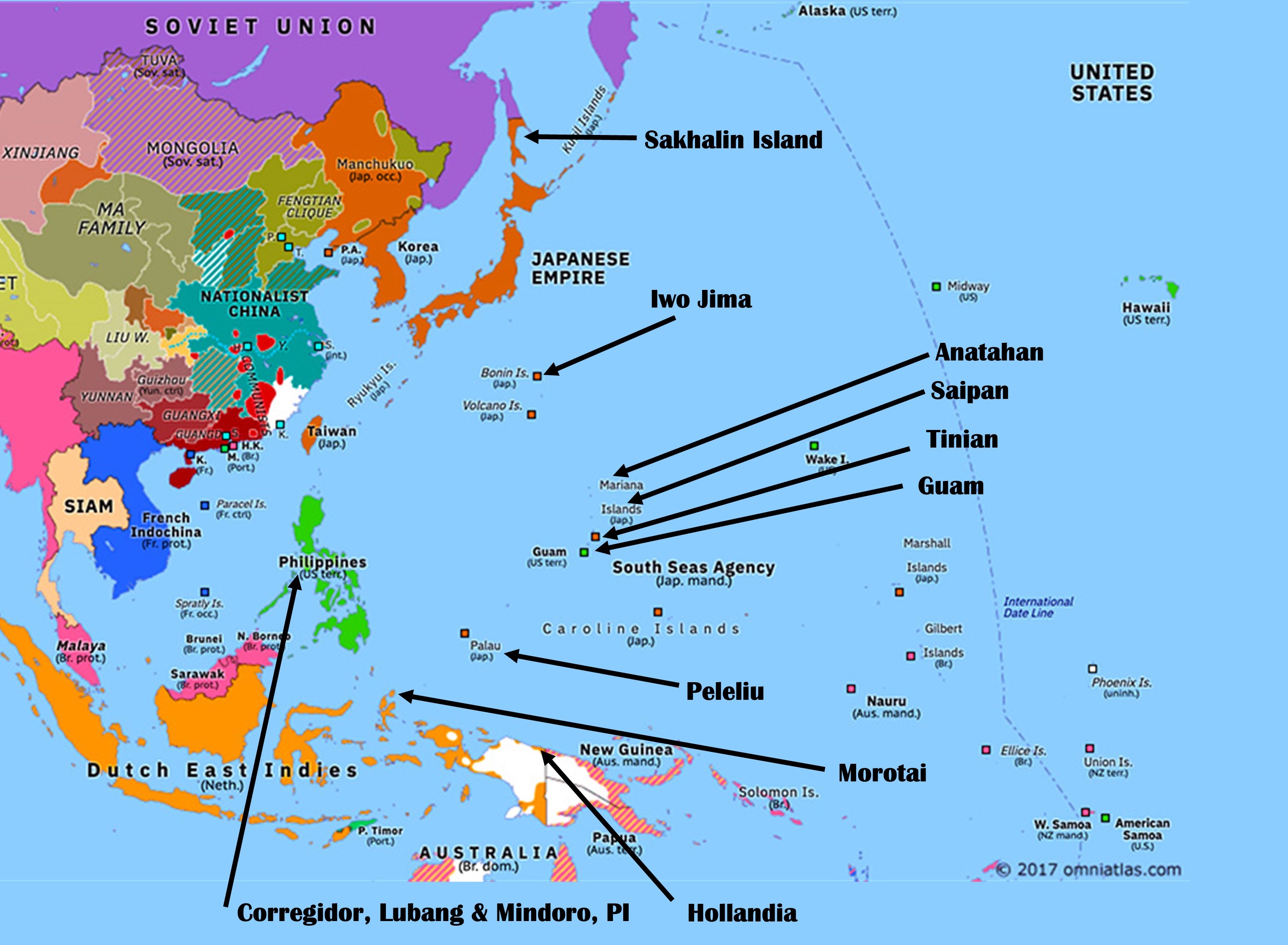

Saipan

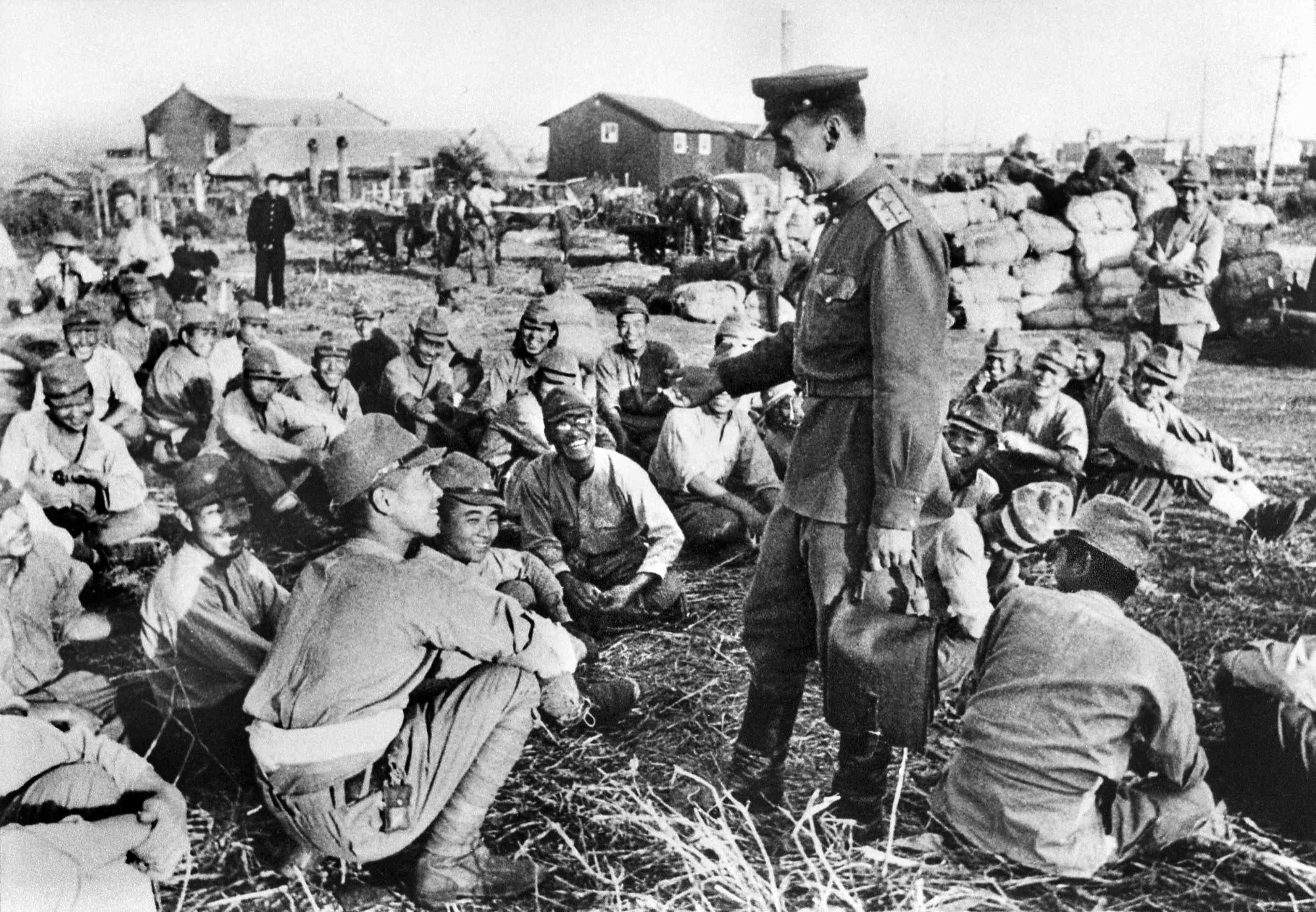

In 1934, Sakae Ōba joined the 18th Infantry Regiment of the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA), as a Ground Officer Candidate, First Class and was sent to Manchukuo (Japanese occupied Manchuria.) In July 1937, the Second Sino-Japanese War erupted, and the 18th Infantry joined the amphibious invasion of Shanghai, China. Early in 1944, the 18th Regiment as part of the 29th Infantry Division was pulled out of Manchuria and re-deployed to the Pacific Theatre as part of convoy Matsu # 1. The convoy of four large transport escorted by three Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) Yūgumo-class destroyers of Destroyer Division 31 was attacked by a U.S. Navy submarine on 29 February 1944 in the Philippine Sea near Saipan.

The USS Trout (SS-202) submarine torpedoed and badly damaged one large passenger-cargo ship and sank the 7,126-ton transport Sakito Maru, which was carrying now Captain Ōba and the 18th Infantry Regiment. The IJN destroyer Asashimo detected the Trout and dropped 20 depth charges until oil and debris came to the surface with the loss of all 81 hands. However, the sinking of the Sakito Maru sent 2,358 IJA soldiers and 117 IJN sailors to the bottom decimating the regiment.

Ōba survived the disaster and was assigned to organize a 225-man medical company composed of tankers, engineers, and medics on Saipan. On the morning of 15 June 1944, U.S. Marines landed on the beaches for the Battle of Saipan. Despite a fierce defense, the Japanese were gradually pushed back with heavy losses. The Japanese commander, LtGen Saitō used Mount Tapochau at the center of the island as his headquarters and final defensive lines. With no re-supply or relief available, the situation became untenable for the defenders, and a final Banzai Charge (or gyokusai (honorable suicide) as Japan’s Military Government called the suicidal human wave attack) was ordered on 7 June. Ōba took part in this the WWII’s largest suicidal attack with over 4,300 soldiers, sailors and civilians. He survived along with 46 other soldiers who he led into the jungle to continue guerrilla actions against U.S. troops.

Ōba insisted that continuing to fight for their country was more important than so-called honorable suicide. Any hope of relief was sunk along with the IJN fleet sailing from the Philippines Islands (PI) were intercepted by the U.S. 3rd and 7th fleets resulting in their decimation in October 1944 in the Battle of Leyte Gulf (considered to be the greatest sea battle of WWII. He refused to believe reports of that maritime defeat and later Japan’s surrender in August 1945 by dismissing photographs dropped by U.S. aircraft of an atom-bomb devastated Hiroshima simply as doctored fakes. The war, he believed, was still there to be won. When medical and other supplies ran out, Ōba would undertake elaborate night raids on U.S. camps, which earned him his nickname, “Fox.” The Marines began conducting patrols in the island’s interior, searching for the Japanese survivors who were raiding their camp for supplies. These patrols sometimes encountered Japanese soldiers or civilians, and when they were captured, they were interrogated and sent to an appropriate prison camp. It was during these interrogations that the Marines learned of Ōba’s name. He cunningly smuggled out POWs to gather intelligence by cleverly replacing them with the same number of his own men counting on the Marines and soldiers to not notice new faces.

At the peak of the “Fox” hunt, the Marine commander devised a plan in which his men would line up across the width of the island and march from the south end to the north. The commander felt that Ōba and his men would have to fight, surrender, or be driven north and eventually captured. Although some of the soldiers wanted to attack, Captain Ōba asserted that their primary concerns were to protect their civilian group and to stay alive to continue their guerilla war. As the line of Marines approached the area, most of the soldiers and younger civilians climbed up to concealed mountain ledges and clung on as the Marines passed. Due to this dragnet, the elderly and infirm Japanese civilians volunteered to surrender.

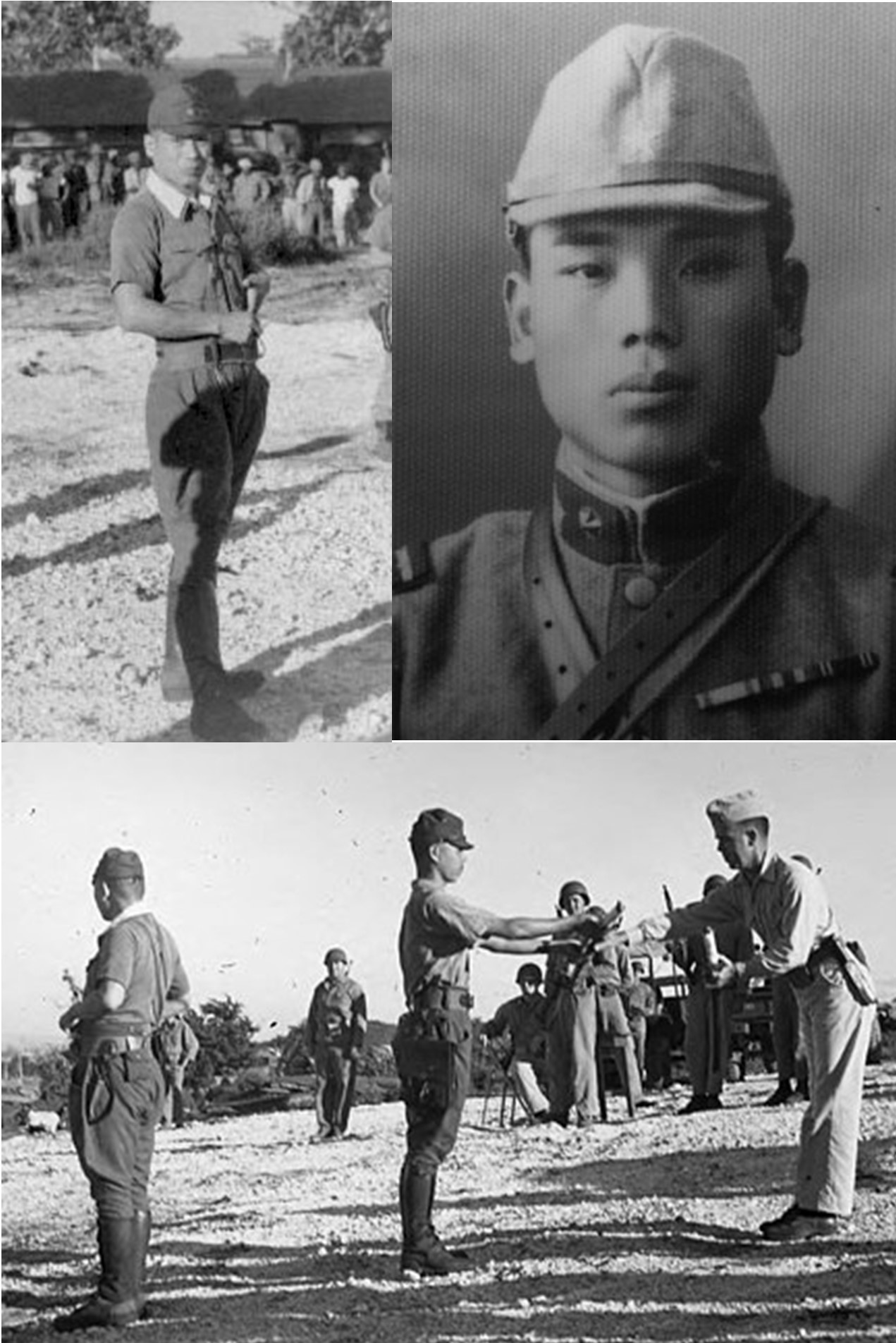

On 27 November 1945, former MajGen Umahachi Amō, commander of the 9th Independent Mixed Brigade during the Battle of Saipan, was able to draw out Ōba by singing the anthem of the Japanese infantry branch. Amō was then able to present documents from the defunct Imperial General Headquarters to the Captain ordering him to stop resistance and surrender themselves to the Americans.

On 1 December 1945, the Japanese soldiers gathered once more on Mount Tapochau and sang a song of departure to the spirits of their battle dead. Ōba then led his people out of the jungle and they presented themselves to the surprised Marines of the 18th Anti-Aircraft Artillery Company. With great formality and commensurate dignity, Captain Ōba surrendered his sword to LtCol Howard G. Kirgis, USMC and his men surrendered their arms and colors. Ōba and his men were the last organized resistance of Japanese forces on Saipan having held out on the island for 512 days, or about 16 months.

By 30 September 1944, the Japanese Army made an official presumption of death for all personnel of unknown status and they were declared killed in action. That included Captain Ōba, and he was awarded a “posthumous” promotion to Major. Upon his return to Japan, Oba was ceremonially stripped of his major rank, which had been awarded in the belief he had died during the banzai charge. Oba took part in that suicidal attack, but because of his decision to fight on, many Japanese labeled him a coward after the war.

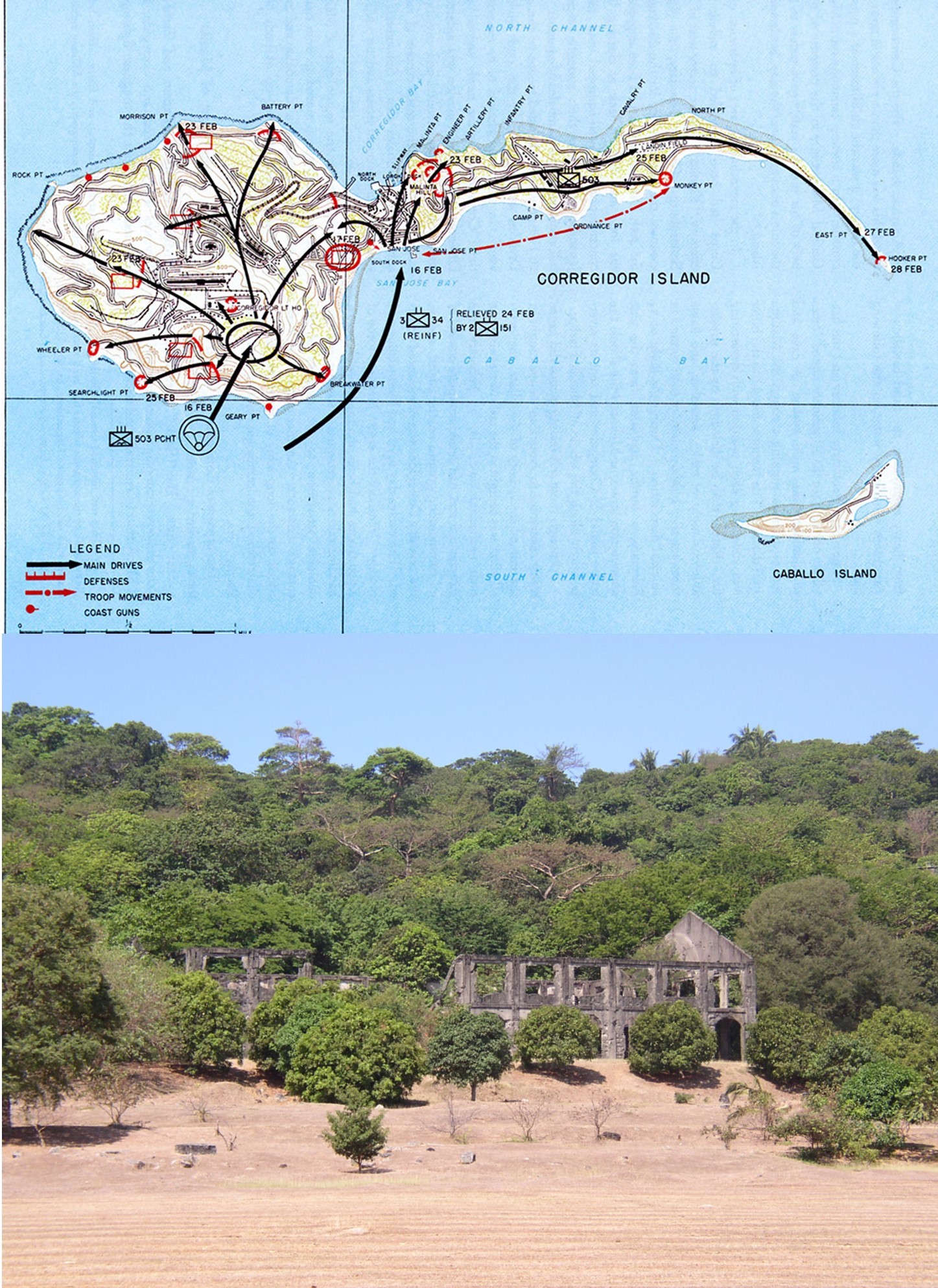

Corregidor & PI

In Feb 1945 the U.S. Army 503rd Parachute Regimental Combat Team conducted an airborne assault as the 3rd Battalion, 34th Infantry Regiment, 24th Infantry Division carried by Landing Craft Mechanized conducted an amphibious assault on the Philippine fortress island of Corregidor, located at the mouth of Manila Bay. Seven months later on 1 January 1946, when a lone U.S. soldier was busy recording the makeshift graves of fallen Americans who had lost their lives retaking the island from the Japanese soldiers and Marines for the U.S. Army Graves Registration.

His work was interrupted when 20 IJA soldiers approached him waving a white flag. They had been living in an underground tunnel built during their occupation but had finally learned that their country had surrendered when one of them ventured out in search of water and found a newspaper announcing Japan’s defeat.

Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) Seaman Noboru Kinoshita survived a torpedoed troop ship off the PI in 1944. When the U.S. Military overran the Japanese in liberating the PI, he retreated into the hills to continue the fight. For eleven years, he lived on lizards, frogs, fruit and wild monkeys in the jungles of Luzon awaiting the day when a victorious Japanese Navy would come to rescue him. That day never dawned, but in November 1955 as he raided a jungle-side sweet-potato patch, Kinoshita was arrested by Philippine police. He asked, "When will my head be cut off?" Told that he would not be executed, but sent home to Japan as a freeman, Kinoshita grew very sad. Deprived of a “bushido” (the moral code of the samurai honor) death by a too-forgiving enemy, he committed suicide by hanging himself rather than "return to Japan in defeat."

In November 1956, four IJA soldiers surrendered on the island of Mindoro in the southern PI: Lieutenant Shigeichi Yamamoto and the Corporals Unitaro Ishii, Masaji Izumida and Juhie Nakano.

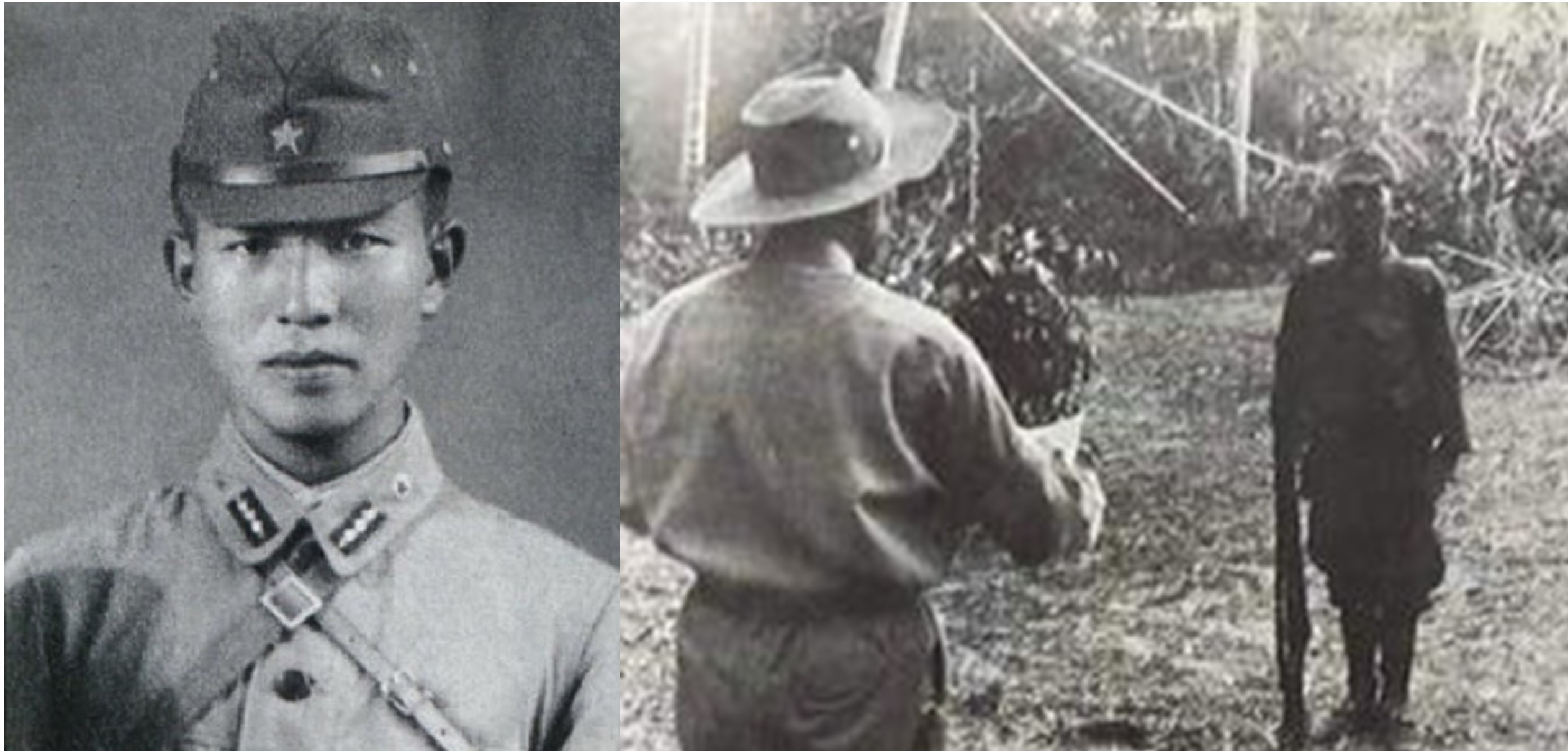

In 1944, as the US fought to retake the Philippines, a 22-year-old IJA Lieutenant, Hiroo Onoda, was sent on a reconnaissance mission to the island of Lubang off Mindoro & Luzon in the western PI. An intelligence officer specially trained as a commando, Onoda was directed to spy on American forces in the area and conduct guerrilla operations. He was ordered to never surrender, but also expressly ordered that, under no circumstances to take his own life in seppuku (ritual suicide.) Once U.S. forces invaded the island, and in short order killed or captured all Japanese personnel, with the exception of Lt. Onoda and three other soldiers. Taking charge, Onoda took to the hills with Private Yuichi Akatsu, Corporal Shoichi Shimada, and Private First Class Kinshichi Kozuka. After the war ended, leaflets were dropped containing a message from General Tomoyuki Yamashita, Philippine Area Commander (on trial for war crimes in Manila) urging the four holdouts to surrender. However, the foursome assumed it was propaganda as they disbelieved the famed “Tiger of Malaya” would ever surrender. However, in 1950, Private Akatsu surrendered himself to Philippine troops. The three remaining soldiers felt betrayed by Akatsu’s action and renewed searches forcing them to became more cautious in their movements.

Two years later, pictures and letters from their families were airdropped, pleading for the three to surrender. Still, the men remained resolute in the jungle. In May 1954, Corporal Shimada died after being shot in a clash with Filipino soldiers search team looking for them. 18 years passed before Private First Class Kozuka met a similar fate in October 1972 during a shootout with local police during a sabotage mission. Despite the loss, Onada stayed in the mountains now alone.

A Japanese adventurer, Norio Suzuki traveled to Lubang Island on 20 February 1974, to find Lt. Onada. After four days of searching, he found him hiding in his mountain hideout as he had for almost 30 years. Suzuki asked Onada why he never gave up and was told that he was waiting for his commander, who promised that he would come back for him and directed him to never surrender.

After finding Onada, Suzuki returned to Japan and reported the situation to the government. Japanese authorities located Onada’s former Commanding Officer, Major Yoshimi Taniguchi. Taniguchi flew to the Philippines to fulfill his promise to his loyal subordinate. On 9 March 1974, the two soldiers met once again, and Onada was officially relieved of duty. He formally surrendered with his samurai sword, a functioning Arisaka Type 99 rifle, 500 rounds of ammunition and several hand grenades, as well as the dagger his mother had given him in 1944 to kill himself with if he was captured.

Despite his team having killed some 30 local Filipino farmers and policemen during his 30-year guerrilla campaign, he was pardoned by then Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos, and became free to return to Japan. He returned to a hero’s welcome in Japan, but admiration for his single-minded devotion to duty was not universal. In Lubang, the inhabitants did not view Onoda as a conscientious and honorable man devoted to duty. Instead, they viewed him as an idiot who had inflicted harm upon the Lubangese, stealing, destroying, and sabotaging their property, and needlessly killing those with whom his band had clashed while stealing or “requisitioning” food and supplies in order to continue fighting a war that had ended decades earlier. A militarist through and through, who believed that the war had been a sacred mission, the 1970’s pacifist Japan to which Onoda returned was unrecognizable to him. He found himself unable to fit in a country and culture so radically different from the one in which he had grown up. Within a year of returning to Japan, Onoda emigrated to Brazil, where he bought a cattle ranch, settled into the life of a rancher, married, and raised a family.

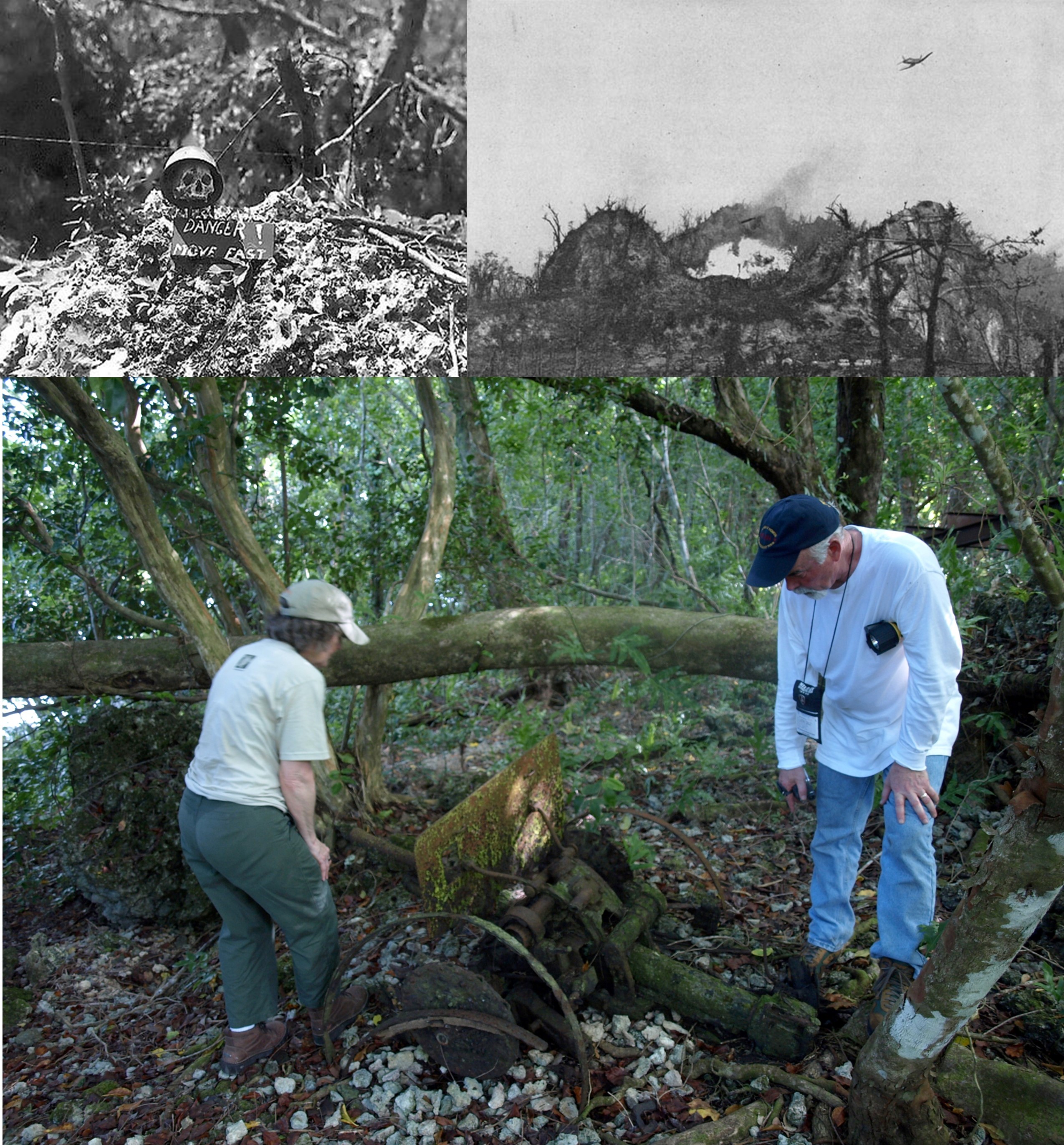

Peleliu

Ei Yamaguchi enlisted in the IJA and became an infantry officer with the rank of Lieutenant assigned to the 2nd Infantry Regiment of the 14th Infantry Division. He fought in mainland China, prior to being sent to Palau. During September 1944, he survived the Battle of Peleliu, holding out in the caves with a group of other Japanese Army and Navy survivors. Lt. Yamaguchi and his 33 soldiers emerged on Peleliu in late March 1947, attacking a patrol of the island’s U.S. Marine Corps detachment with hand grenades and rifle fire believing the war was still being fought. Luckily, there were no Marine casualties. At that time, only 150 Marines were stationed on the island, with 35 civilian dependents. On 19 March 1947 at the request of Rear Admiral C. A. Pownall, USN (Commanding Officer (CO), Marianas Naval Forces) 31 Marine reinforcements from Pearl Harbor and 40 more from Guam were flown to Peleliu Airfield to bolster the garrison. On 21 March another 15 more were to be flown to join them and war dogs were requested.

These Reinforcement were called in to hunt down the Japanese that were believed to have hidden in the island’s north and infiltrated southward to occupy caves on Umurbrogol (Bloody Nose Ridge.) To reduce casualties, RADM Pownall allowed Japanese POW RADM Michio Sumikawa (former CO 4th Fleet) who was detained at the Guam stockade and testifying as a witness in the Guam War Crimes Trial to be flown to Peleliu in an attempt to reach the holdouts. Accompanied by a Palau native, Sumikawa's initial attempt to communicate with the holdouts was unsuccessful as he was unable to locate them to make direct contact. Before departing, he left a personal letter asking them to surrender. Later, the Japanese holdouts responded in a note saying the effort was a hoax using a Nisei (second generation Japanese-American) to simulate a Japanese officer and requested to personally meet the admiral.

Before his second effort, RADM Sumikawa stated: "They still are not convinced that all is lost. I want to tell them the truth because of my personal feeling to save these men and the possible sick and wounded among them. I have promised Admiral Pownall to give my best cooperation. There are certain risks but one can't undertake a mission of this nature without some uncertainty. I hope I will be successful for their sake and to save bloodshed."

On 31 March 1947 Sumikawa escorted by a USN Commander from the Office of Naval Intelligence was flown back to Peleliu for a second attempt to convince them to surrender this time with a loudspeaker. He brought his hanko (personal seal), Japanese newspapers, photos of himself to establish his identity and copies of the Japanese instrument of surrender signed by Emperor Hirohito plus photos of Japanese soldiers being repatriated to Japan.

This trip the meeting was successful in convincing the holdouts that the war was indeed over. The band emerged from the jungle in two groups in late April, led by Yamaguchi who turned over his sword and unit's battle flags. The work prevented a repeat of the bloody cave to cave fighting used three years earlier to burn or blow the Japanese out of their cave strongpoints.

Iwo Jima

On 6 January 1949, two 20th Air Force Corporals picked up a pair of hitchhikers on the island’s loop road on the way back to the motor pool. The two Air Force communicators decided they were from the Chinese ships that were removing scrap metal from the battle as they pair did not understand English. They stopped at the motor pool to get a new trip ticket and when they returned the men were gone. Later at lunch they learned that the supply sergeant had captured two Japanese soldiers near the base flagpole. The sergeant approached them and recognized then as Japanese. He took them to the Island Commander, and then the process began to find out who they really were.

After an inquiry, the Air Force had captured Yamakage Kufuku and Matsudo Linsoki, two IJN machine gunners who lived in a cave off the loop road not too far from the “Flag Raising” rock where they had been picked up. Upon examination of their cave a lot of mysteries were solved. Most of our canned ham that had gone missing for the 1948 Christmas dinner was found, plus the missing flashlight batteries plus things missing from the family housing area were found in the cave.

This was their second cave as their first was very near the transmitter antenna farm. They had kept cave explorers away by using barbed wire entanglements in the cave entrances, a warning that marked the cave as unsafe.

Anatahan Island “Lord of the Flies”

In June of 1944, a Japanese convoy was sunk off Anatahan, a small Marianas Island about 75 miles north of Saipan. 31 soldiers and sailors swam to Anatahan, where they were taken in by the Japanese head of a coconut plantation and his wife. American forces invaded the Marianas shortly thereafter, seizing the main islands and bypassing the smaller ones. The Japanese on Anatahan ended up cut off and isolated from the outside world. Conditions grew dire on the resource-poor island, and the castaways barely survived by consuming coconuts, lizards, bats, insects, taro and wild sugar cane.

Salvation fell from the skies on 3 January 1945, when a damaged B-29 bomber, returning from a raid on Nagoya Japan, crashed killing its entire crew. Scavenging the plane wreck, the castaways fashioned the plane’s metal into useful items, such as knives, pots, and roofs for their huts. Parachutes were turned into clothing, oxygen tanks were used for storing water, machinegun springs were fashioned into fishing hooks, nylon cords were used as fishing lines, and some pistols were also recovered. Life remained difficult, but the B-29 crash saved the castaways, who had been facing slow starvation until aid fell from the sky.

The U.S. Navy found about the castaways when they sent a boat of Chamorros to recover the remains of the Army Air Force crewmembers from Saipan. The Chamorros reported about 30 armed Japanese on the island so pamphlets were dropped but the Japanese believed it was “fake news” and refused to surrender numerous times. So, the U.S. Navy didn’t feel it worthwhile to root them out.

Anatahan’s demographics further complicated survival as the castaways’ plight was far worse than the male-female ratio on “Gilligan’s Island.” Unsurprisingly, 31 men stranded for years on a small island that contained only one woman led to trouble, as the men competed for her affections. The woman, Kazuko, had arrived with her husband in 1944, but he disappeared in mysterious circumstances soon after the castaways washed ashore. Soon, she remarried but another castaway shot and killed her new husband, only to have his own throat slit soon thereafter by another aspiring beau.

Kazuko became a full-blown femme fatale, transferring her affections between a series of lovers. The distilling of “tuba” - fermented coconut wine didn’t lessen jealous alcohol-fueled rage. Eventually there were 12 deaths on Anatahan, as the men fought for the affections of the island’s sole female. One of Kazuko’s wooers had been stabbed by jealous rivals on 13 separate occasions, yet returned to his amorous pursuit as soon as he recovered from each attempt on his life. Finally, in 1950, Kazuko emotionally or physically tired, flagged down a passing American ship, and asked to be taken off the island. This brought on another round of air-dropped letters and proof of the wars end.

Finally in June of 1951, A U.S. Navy plane that flew over the island spotted 18 Japanese soldiers on the beach waving white flags of surrender. The Navy dispatched a seagoing tug, the USS Cocopa (ATF-101), to the island in hopes of picking up some or all of the soldiers without incident. After a formal surrender ceremony on the beach all of the men were brought onboard.

The Japanese occupation of the island inspired the racy 1953 film “Anatahan” and the 1998 novel “Cage on the Sea.”

Tinian

Many IJA soldiers & IJN Marines remained hidden on Tinian after the U.S. Marine Corps 2nd & 4th Divisions liberated the island in August 1944. “Toughy,” a IJN sailor who was wounded when his cave was blown up, recovered in a U.S. military hospital and became an ally to Marines and Army Intelligence who persuaded Japanese to come out and surrender. Sometimes Japanese would surrender to B-29 crews preparing to fly missions.

The last IJA holdout on Tinian, was captured in 1953 and was not a soldier but a civilian native Japanese who worked for NKK, the largest sugar producer in the Marianas.

Dutch New Guinea - (now part of Indonesia)

In 1955, four Japanese airmen surrendered at Hollandia in Dutch New Guinea: Shimada Kakuo, Shimokubo Kumao, Ojima Mamoru and Jaegashi Sanzo. They were the survivors of a bigger group.

Morotai – (island in the former Dutch East Indies located: between Indonesia-PI-West Papua)

In 1956, nine IJA soldiers were discovered and sent home from Morotai.

Private Teruo Nakamura (born: Attun Palalin), was born in the then Japanese possession of Formosa (today’s Taiwan) in an aboriginal tribe. He was conscripted into a colonial unit in 1943, and posted to Morotai Island in the Dutch East Indies (present day Indonesia) in 1944. Soon after his arrival in Morotai, American and Australian forces liberated the island breaking organized IJA resistance while inflicting heavy losses on Japanese units. The survivors fled into the jungle to conduct guerilla operations but they suffered even more attrition from starvation and disease. He stayed with a group until 1956 before setting out on his own to hack a small plot from the rainforest.

Nakamura’s hut was spotted by an Indonesian Air Force pilot in the Morotai jungle in 1974. Honoring a Japanese embassy request, the Indonesian military launched a search expedition later that year. Indonesian soldiers finally tracked him down and captured an emaciated Nakamura on 18 December 1974, and flew him to Jakarta to receive his first medical care in three decades. Compared to Hiroo Onoda whose holdout had ended a few months earlier, and who was lionized and celebrated as a paragon of conscientious devotion to duty, Nakamura garnered relatively little attention in Japan. Onoda was an ethnic Japanese citizen, but Nakamura had been a colonial soldier from Taiwan. Although he expressed a wish to be repatriated to Japan, he was denied citizenship and was sent to Taiwan instead. Teruo was “the last of the last” of the Japanese holdouts, outlasting the more famous Hiroo but his service only earned him $227 backpay from Japan versus $160,000 for Onoda.

Russia

Ishinosuke Uwano was drafted into the IJA during WWII, and was posted to the garrison of the then-Japanese southern half of Sakhalin Island in 1943. In August of 1945, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan and successfully invaded and seized the southern half of Sakhalin, despite fierce Japanese resistance.

After Japan surrendered, the Soviets shipped the Sakhalin garrison survivors to POW gulags in Siberia, where they labored for years, until they were slowly repatriated to Japan in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Uwano was not included in their numbers. In the years following the war, his family received reports of scattered sightings of him in Sakhalin, where it was suspected he had gone into hiding in its rugged and harsh terrain after he found himself cut off following the Red Army’s advance. The last reported sighting of Uwano in Sakhalin was received by his relatives in 1958, a full 13 years after the war had ended.

42 years later in 2000, his family recorded his disappearance in accordance with a law for registering those Japanese military personnel who did not return after WWII as war dead. At some point, it seems he surrendered to the Soviets. Probably due to the Soviet Cold War paranoia, love of excessive secrecy or just good old fashioned communist bureaucratic ineptitude neither the Japanese government nor Uwano’s family were notified.

Once released from Soviet imprisonment, in 1965 he settled in the Soviet Union instead of returning to Japan. He got naturalized as a citizen, ended up living in the Ukrainian SSR, married, and had three children. It was only in 2006 at 83 years old after he asked Ukrainian friends to contact the Japanese government, which then sent officials to interview him in Kiev, that the story of his survival was known in Japan.

When he sought to return to Japan in order to pray at his parents’ graves, reconnect with family members, and see one last time his first country’s famous cherry blossoms, it emerged that, because he had been declared dead in 2000, he was technically no longer considered a Japanese citizen. He was allowed to visit Japan, but only traveling on his Ukrainian passport. Not that Uwano minded. As he told reporters, he had no plans to live in Japan. “Ukraine has become my homeland,” he said.

Guam

On May 11, 1948, the Associated Press reported that two Japanese soldiers surrendered to civilian policemen on Guam.

Private Bunzo Minagawa held out from 1944 until May 1960 on Guam when he was captured by a local woodsman and turned over to local authorities. Sergeant Masashi Ito, Minagawa's superior and an IJA machine-gunner, surrendered four days later, 23 May 1960.

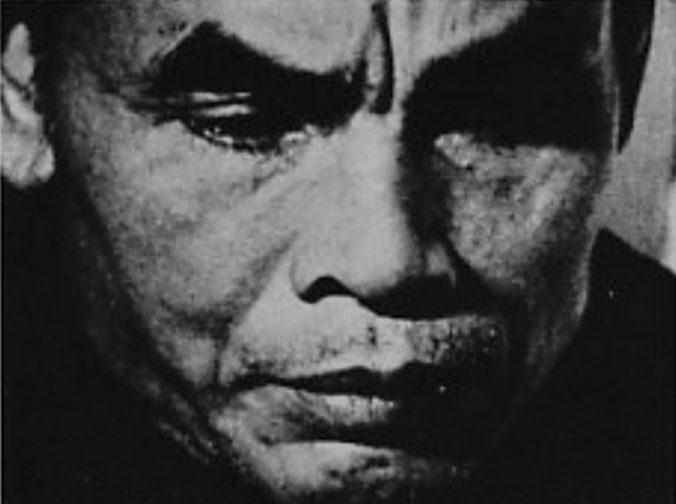

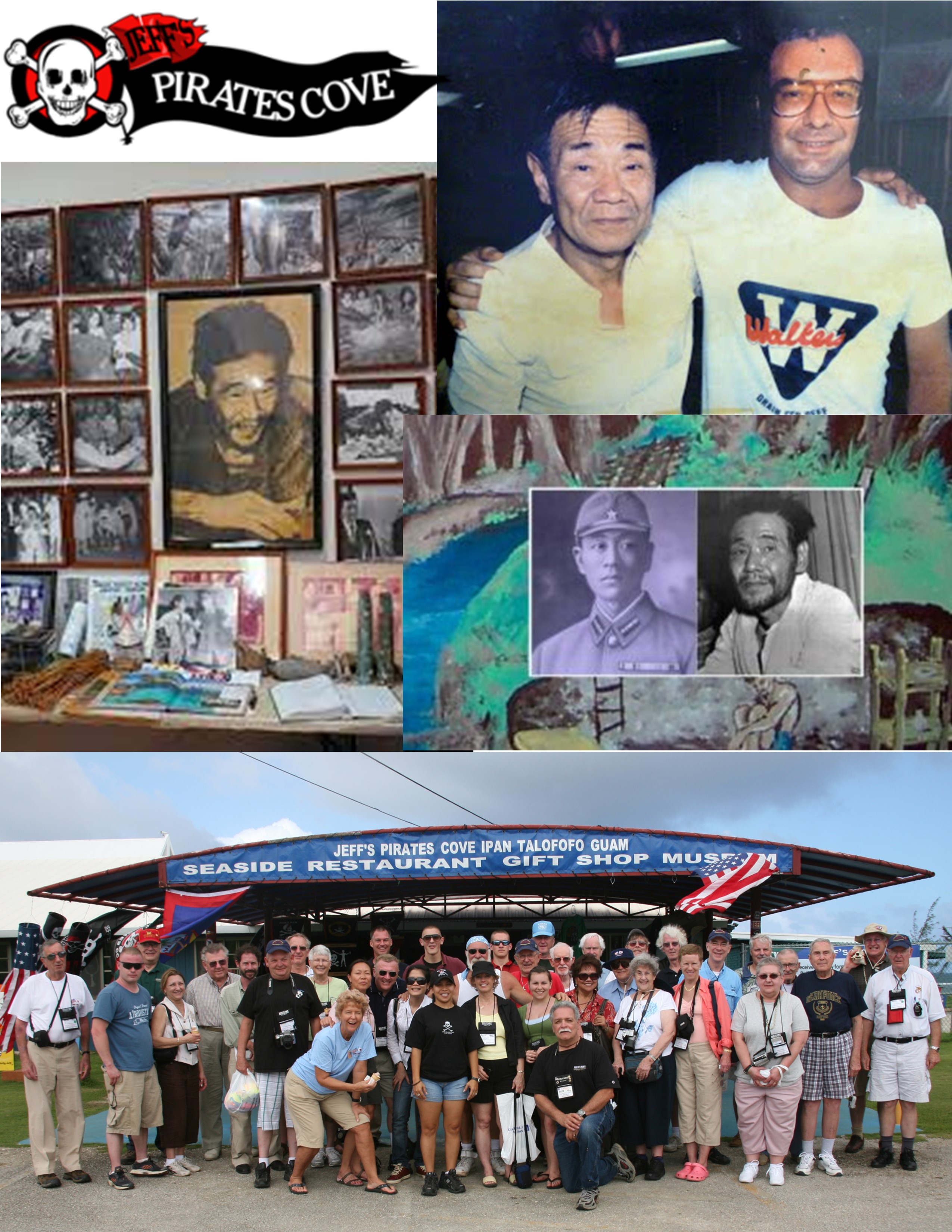

An IJA Sergeant, Shoichi Yokoi had been posted to Guam in 1943. A year later, when the island was liberated by U.S. forces, he fled into the jungle with nine other Japanese soldiers, who refused to surrender. The group gradually dwindled over the years to a trio. In 1964 Yokoi’s last two companions died of malnutrition and disease leaving him the last holdout on Guam. The two soldiers were hiding out in the same area and the only humans Yokoi had any contact with. The three Japanese soldiers agreed that they should limit their contact with each other to avoid detection. Yokoi buried his compatriots in a cave and would direct authorities to this site soon after he was captured.

Yokoi survived in the jungle, spending his days hiding in an underground spider hole, only emerging at night to hunt lizards and rats, trapping shrimp and fish gather tubers and snails. Yokoi was able to keep from getting ringworm, lice infestations, and other infectious jungle diseases by bathing frequently and thoroughly. He was remarkably healthy when he was found. His movements were restricted to the night hours and the thick jungle in that area helped him remain hidden.

In 1972, two local men, Jesus Duenas and Manuel DeGracia were out checking fish traps when they saw Yokoi near a small river. At first, they thought he was a young man from their village who sometimes roamed the jungle and were about to move on. Suddenly Yokoi, assumed they were about to attack him and made the decision to attack them first. They subdued him before carrying him out of the jungle and back to civilization, where his astonishing story finally came out. On 24 January, after almost 28 years from the Allies regaining control of Guam in 1944, Yokoi stepped out of the Talofofo River Valley jungle into the jet age.

Yokoi was brought out of the jungle tied and only slightly bruised as his captors deserve credit for that. Japanese stragglers were ruthlessly hunted down and killed by local men who despised the soldiers and sailors as a result of the atrocities committed by Imperial Japanese forces during Guam’s occupation. His cave entrance as well as the one where his two compatriots were buried were cleverly concealed and absolutely impossible to find if you didn’t know exactly where to look. Two grenades and a 155mm artillery shell were the only weapons found in the caves. Yokoi’s twenty-eight years of hiding and deprivation can be seen as testimony to the strength of the human spirit, or as just another sad episode in the ongoing saga of warfare.

By the time Yokoi was returned to Japan, he was famous and unlike most other stragglers, he had little trouble adjusting to life in the new Japan. Despite his years of isolation in a Pacific jungle, his mind was still sharp as he correctly calculated the time that had passed and knew it was 1972 when he was captured. He swiftly parleyed his celebrity into a successful media career, becoming a popular TV personality and an advocate for austere living. Sergeant Yokoi returned to Guam several times after his capture and ate at Jeff’s Pirates Cove where Military Historical Tours always stop for a great lunch and seaside setting. https://miltours.com/index.php?route=information/information&information_id=125

He died of a heart attack in 1997, and was buried under his gravestone that had been commissioned by his mother in 1955, when Japan officially declared him missing in action.

Epilogue

There have been some straggler reports since, the most recent in 1980 by a Japanese newspaper reporting that IJA Captain Fumio Nakahara was still holding out but he was never found:

“Japanese searchers have found positive traces of a Japanese sergeant believed to still be hiding out in Philippine forests 35 years after the Japanese surrender in World War II, reports said Friday. The search team, headed by retired Capt. Isao Mayazawa, said they believed they had found the mountain hut where the straggler, believed to be Sgt Fumio Nakahara of the intelligence unit of the defunct Japanese Imperial Army, lives…The hut is on a rugged peak of Mount Halcon in Oriental Mindoro, 100 miles south of Manila, near a cultural minority tribe village…Mangyan tribesmen had told the team the man residing in the isolated hut near their village was known to them as "Mondoka," whom they described as "chinky eyed, white skinned and well disciplined. The hut was said to be quite different from an ordinary Filipino mountain hut in that it had two doors and was located at a vantage point to obtain a panoramic view of the surrounding terrain. Searchers said the straggler appeared to have very good relations with most of the Mangyan tribesmen, who were generally tight-lipped about "Mondoka."”

MHT hits four of the spots in this blog: 78th Anniversary Iwo Jima Reunion of Honor (20 - 27 March 2023) (miltours.com)