Blog 11/18/2020 - The Battle of Beecher Island

MHT Blog November 18, 2020 - Battle of Beecher Island – Colorado

“Maj Forsyth’s Irregular Cavalry Company vs a Northern Cheyenne, Arapaho & Oglala Sioux Indian Band”

Yesterday all I could think about was the smell of unburied dead men in the hot sun and rotting horse flesh with the constant buzz of swarming masses of black flies drawn by the two. This was the scene at the Battle of Beecher Island. It had been 40 years since I had first heard of this battle in a military history class and had forgotten how 50 frontiersmen had been put in such a nightmarish dilemma. On the 17th of September, 1868, some have said it was the hardest battle fought between Frontiersmen and the Plains Indians in the annals of the West.

For months in Nebraska, Colorado and Kansas a marauding band of Northern Cheyenne, Arapaho and Oglala Sioux Indians had been murdering settlers and pioneers. Cavalry troopers were at a premium in the post-Civil War West and when dispatched to pursue they usually arrived too late at the scene and just buried the bodies. Major General Philip Sheridan decided to try a new tactic. He ordered his aide, Major George Alexander Forsyth of the 9th Cavalry, also a decorated Civil War Veteran, to raise a volunteer company of fifty experienced frontiersmen, to track and deal with the hostile Indians bands using their tactics, rather than those of the traditional Army.

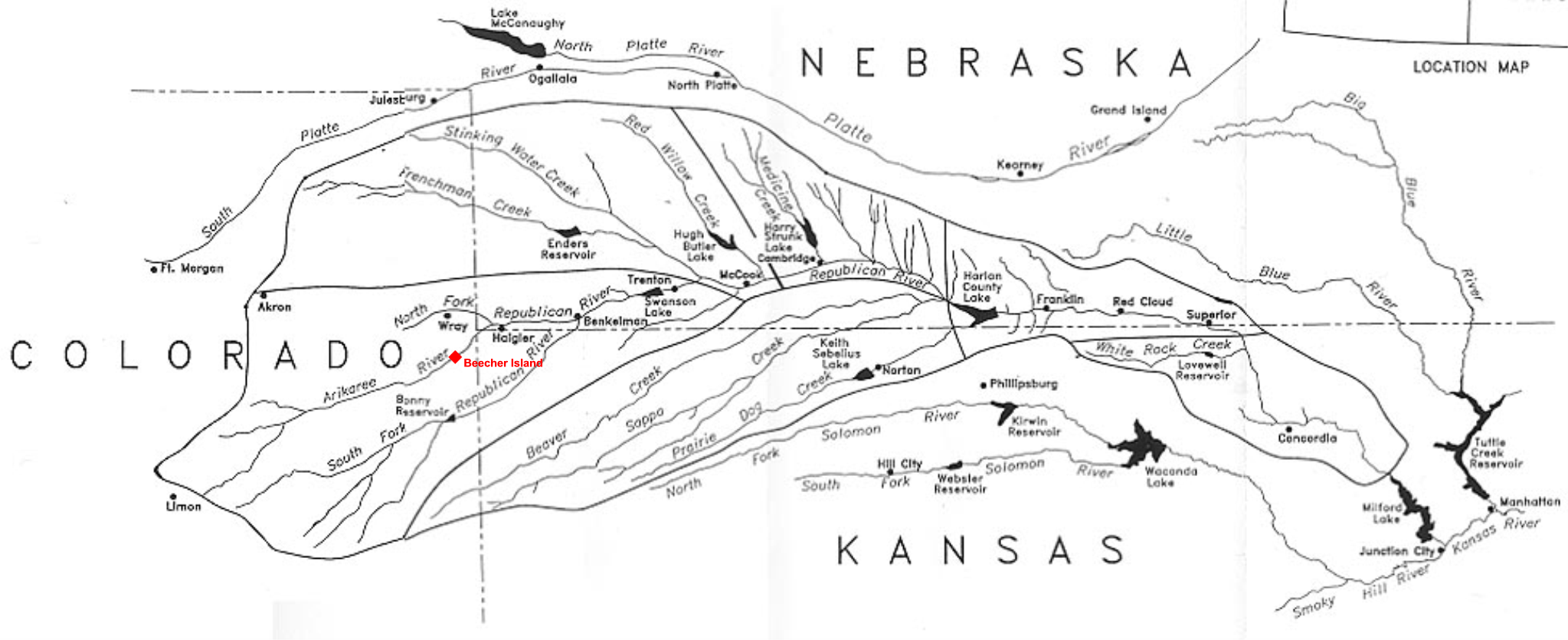

Early in September, the Forsyth unit moved out from Fort Wallace, Kansas tracking the Indians trails into the new state of Nebraska along the Republican River. During the afternoon of September 16th, the scouts had tracked the Indian into the Colorado Territory and Major Forsyth prepared to attack the Indians the next day but posted extra sentries that evening being near some villages. At dawn, the men were up and saddling their horses when there came a volley of warning shots from the sentries followed by the yell and rush of Indians. Roman Nose, a war leader of the Cheyenne, had hoped to catch the scouts asleep and their horses unguarded. He was unable to stampede the horses and leave the soldiers on foot in the open where they could attack on horseback. However, they found the scouts horses saddled and ready to return fire forcing the Indians back outside rifle range. The hills on both sides of the little valley swarmed with Indian warriors, more than the scouts had ever seen massed before.

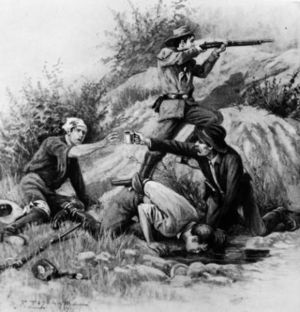

Major Forsyth saw the tactical situation at a glance. A few hundred yards away in the middle of the Arickaree fork of the Republican River was a sandbar having one cottonwood tree and a growth of willows bushes, the only cover in the valley. Forsyth led the scouts as they dashed through the shallow water to the sandbar. Every man tied his horse as best as he could to a bush dropped to a knee held his rifle in one hand and dug a defensive hole in the sand with the other. The withdrawal to the sandbar was a surprise to the Indians. Roman Nose had counted on a quick and complete victory but now the small contingent made a fort out of the little island. The Indians filled up the banks on both sides of the river and fired a storm of bullets and arrows. A number of the scouts were killed and wounded and the poor horses took the brunt of the casualties and became breastworks for the sandbar fort. The sandbar was named Beecher Island for Major Forsyth’s Executive Officer, Lieutenant Fredrick H. Beecher killed during the attack.

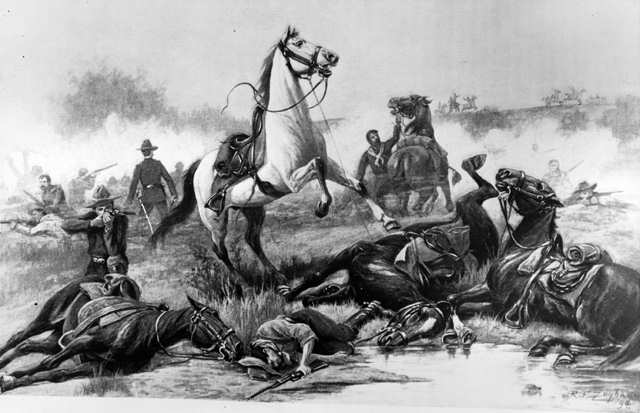

At noon Roman Nose called a gathering of Indians from all parts of the battlefield on the hill above in the scouts. The scouts all knew the leader, as Roman Nose was over six feet tall, one of the tallest Indians on the plains and one of the fiercest chiefs. The war council broke up and Roman Nose led a body of mounted young warriors down into the valley. They formed in a line facing Beecher’s Island as the plan was now clear. The 200-300 mounted braves were to charge the island while the rest of the Indians crept up close to fire as fast as they could to keep the scouts heads down in their sand fighting holes. What Roman Nose hadn’t accounted for was the frontiersmen all being armed with the new Spencer 1865 Carbine .50 caliber.

In 1867, Brigadier General James F. Rusling of the Quartermaster's Department recommended exclusive use of the carbine by cavalry units against mounted Indians raiders after completing a one-year tour of the western territories. One of the advantages of the Spencer was that its ammunition was waterproof and durable enough to stand the constant jostling of long patrols owing to the new technology of metallic cartridges. The Indians had one-shot rifles but had never seen one that could shoot seven times without loading. Luckily for the scouts Major Forsyth had armed his patrol like a US Cavalry unit.

On came the line of Indians, yelling and whipping their horses, as they reached the river bank the scout’s rifles opened up and groups of riders fell from their ponies. On they rode into another volley, a third and a fourth as more Indians fell. Roman Nose was hit and fell from his horse mortally wounded and the Indian line broke and scattered. Major Forsyth tended to the wounded of which he was one, mindful of the Indian sharpshooters hidden on and firing form the banks.

The battle now changed to a siege, with the loss of Roman Nose there would be no more attempts to take the island by storm. Starving the scouts became the Indian plan as Forsyth’s men had lost their pack mules with all their provisions in the dawn attack. They had nothing but muddy river water to drink and their dead horses to eat which made them sick as they rotted. The first attempt to escape to bring help failed as the Indians were too watchful but the second one crept away to try to reach Fort Wallace. For more than a week they lay in their sand fighting holes, drank river water and ate horse meat. The sun was hot and the smell of the dead was overpowering. Another charge might have overrun the sandbar but maybe the frontiersmen and Indians alike had been unnerved by the harrowing wails of the Indian women for their dead warriors. The tribes preferred to starve the scouts and harass with snipers.

On September 25th, there was a dust cloud far off on the prairie. It grew larger until the scouts saw that it was Lieutenant Colonel Louis H. Carpenter leading Troop H & I of the 10th Cavalry Regiment with a doctor and an ambulance. They knew then that the battle and siege of Beecher Island were over. The Indians fled as the soldiers approached to relieve the isolated scouts. Ironically, Brigadier General Custer said that the Arickaree fight was the Plains greatest battle not knowing he would be the perpetrator of the battle that would forever define the Great Plains Indians Wars. The scouts lost six KIA & 16 WIA while one Indian participant said their losses were near 100.